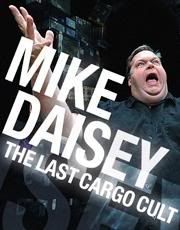

To my delight, American monologist Mike Daisey made a swing through the Sydney Opera House with his show, The Last Cargo Cult, last week.

(photo from www.syndeyoperahouse.com)

(photo from www.syndeyoperahouse.com)I’ve long admired Daisey from afar. I followed with fascination when he burst onto the theatre scene with his indictment of his time at Amazon, 21 Dog Years. I was in grad school when a Youtube video showed a student group storming out of one of his performances, which we grads debated with interest. I read reviews of his How Theater Failed America, as I worked at a regional theatre. He seemed to be hitting upon some highly insightful ideas about the failings of the American regional theatre movement. In short, I’ve been thinking that this guy is pretty darn bright and funny for quite some time. Sadly, I’d never been geographically positioned to see him at work.

So, his name was all I needed to snatch up tickets for his show in Sydney. The Last Cargo Cult turned out to be a fortuitous offering. My partner in crime is a financial analyst. I peddle in the business of theatrical storytelling. This show was fun for the whole family.

For the uninitiated, Mike Daisey is a solo storyteller, in the tradition of Spalding Gray or Eric Bogosian. He sits at a desk with notes (no fully realized script exists) and, perhaps, a glass of water. He’s a big guy, armed with a nuanced palette of gestures and expressions. His voice booms and whispers and coaxes and chastises. His command of the English language, both formal and informal, is mesmerizing. He creates pictures with story and metaphor that become as vivid in the mind’s eye as a fully staged and costumed theatrical production.

The Last Cargo Cult derives its name from a South Pacific tribe that annually celebrates John Frum Day, based on a mythical American figure. The celebration includes dance, music, and theatre aimed at retelling the history of America (as they know it). Daisey visited the island of Tanna to witness the event, armed with a duffel bag of blue jeans, and came away with a starting place for this monologue. This part of the story is every bit as bizarre and intriguing as it sounds, but it’s really just the lens for looking at something much larger, which is the Western world’s absolute obsession with money … more than obsession. Daisey convincingly theorizes that money is our first religion: The thing that drives us every moment of our day. The thing that defines the character of most of our human relationships. It is a religion based on a “want” within our souls, and is void of all ethics and morals.

Enter scene: September of 2008 and the collapse of Lehman Brothers. We Americans suddenly learned about credit default swaps and derivatives (a concept so ridiculous that Daisey says it took him three months to understand them … “three months I will never get back”). I certainly recognize the schadenfreude that Daisey describes, as we poor artists watched our previously well-to-do brethren suddenly cutting back, bringing their lunches to work, and struggling to make the mortgage payments. However, after the smugness, comes the realization that our entire financial system (our religion) is collapsing. Daisey demonstrates how the system is essentially a pyramid scheme that layfolks are not meant to understand. Once the numbers and vocabulary become too difficult for us to comprehend, we abdicate responsibility. In other words, no one “sane” was at the wheel when Lehman collapsed. And, truthfully, we continue to stare blank-faced at the size of the American national debt because, really, who understands what hundreds of trillions of dollars really are?

Daisey makes our relationship to money personal by creating a real-life commodity exchange within the theatre, which I won’t spoil here. He holds his audience accountable for doing more than simply sitting in the dark. The exchange becomes both heated and emotional … we are asked to think about our relationship to the symbolic slips of paper that are money more deeply than we typically ever do.

There are a few plays around right now that deal with the financial meltdown (here in Australia, they call it the Global Financial Crisis - GFC). In fact, we recently saw a beautiful production of David Hare’s The Power of Yes at Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre, which I liked very much. But in that piece, Hare angrily indicts the bankers for letting this happen. In other words, he blames “them.” Don’t get me wrong, I am full of strong feelings about where the bankers who caused this can go in this life and the next, but I found myself much more moved by Daisey’s piece because he makes it about “us.” The “us” that fell in deep want for a life full of “awesome shit.” The “us” that holds our bank account balance the most important number in our lives. The “us” that have recused ourselves from understanding the instruments by which we are being ruled.

When we bought our tickets for this show, Partner-in-Crime and I wondered whether Australian audiences would be able to get much out of this piece. After all, Australia is doing quite well in the world marketplace. I struggled with even writing this review. This is a blog about Australia, so why talk about an American show about an American crisis? But, I did not have to walk more than a block from my house to realize that it is an Australian story, too.

Sydney is in the midst of an amazing housing bubble. At an expat meetup, we heard story after story of renters viewing studio apartments with 30 - 40 other potential tenants, all with cash deposits in hand, desperate to be chosen. Single bedroom apartments turn around for half a million within a week. I lived in Florida. I’ve seen this before. We can all enjoy the giddiness, until we suddenly don’t anymore. But, as Mike Daisey tells us, we cannot act surprised when the party ends. We stand warned. We are all in this together. Or, as Mr. Daisey so succinctly augered about the Australian housing bubble during the talkback, “you guys are fucked.”

Finally, for the artists: Daisey was so generous with his time and ideas in a post-show discussion, where he amiably entertained a small group of us who stayed. One attendee, who identified herself as a financial reporter, asked why the financial crisis was such a “trendy” topic in the theatre (what with up to three plays about it going on right now). He turned the question upside down and asked why the topic was not more popular. As artists, it is our job to explore the important and complicated issues of our day. Is this ongoing crisis not the most important and most complicated? Should we not be providing the intellectual and moral flashlight in the dark forest world full of hedge funds, repos and CDOs? Go to work, artists. I, for one, cannot wait to see what more you can show us.

No comments:

Post a Comment